freeCodeCamp

“Ruby is simple in appearance, but is very complex inside, just like our human body.” — Matz, creator of the Ruby programming language

For me, the first reason is that it’s a beautiful language. It’s natural to code and it always expresses my thoughts.

The second — and main — reason is Rails: the same framework that Twitter, Basecamp, Airbnb, Github, and so many companies use.

Ruby is “A dynamic, open source programming language with a focus on simplicity and productivity. It has an elegant syntax that is natural to read and easy to write.” — ruby-lang.org

Let’s get started with some basics!

You can think about a variable as a word that stores a value. Simple as that.

In Ruby it’s easy to define a variable and set a value to it. Imagine you want to store the number 1 in a variable called one. Let’s do it!

one = 1 How simple was that? You just assigned the value 1 to a variable called one.

two = 2 some_number = 10000 You can assign a value to whatever variable you want. In the example above, a two variable stores an integer of 2 and _somenumber stores 10,000.

Besides integers, we can also use booleans (true/false), strings, symbols, float, and other data types.

# booleans true_boolean = true false_boolean = false # string my_name = "Leandro Tk" # symbol a_symbol = :my_symbol # float book_price = 15.80 Conditional statements evaluate true or false. If something is true, it executes what’s inside the statement. For example:

if true puts "Hello Ruby If" end if 2 > 1 puts "2 is greater than 1" end 2 is greater than 1, so the puts code is executed.

This else statement will be executed when the if expression is false:

if 1 > 2 puts "1 is greater than 2" else puts "1 is not greater than 2" end 1 is not greater than 2, so the code inside the else statement will be executed.

There’s also the elsif statement. You can use it like this:

if 1 > 2 puts "1 is greater than 2" elsif 2 > 1 puts "1 is not greater than 2" else puts "1 is equal to 2" end One way I really like to write Ruby is to use an if statement after the code to be executed:

def hey_ho? true end puts "let’s go" if hey_ho? It is so beautiful and natural. It is idiomatic Ruby.

In Ruby we can iterate in so many different forms. I’ll talk about three iterators: while, for and each.

While looping: As long as the statement is true, the code inside the block will be executed. So this code will print the number from 1 to 10:

num = 1 while num 10 puts num num += 1 end For looping: You pass the variable num to the block and the for statement will iterate it for you. This code will print the same as while code: from 1 to 10:

for num in 1. 10 puts num end Each iterator: I really like the each iterator. For an array of values, it’ll iterate one by one, passing the variable to the block:

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].each do |num| puts num end You may be asking what the difference is between the each iterator and for looping. The main difference is that the each iterator only maintains the variable inside the iteration block, whereas for looping allows the variable to live on outside the block.

# for vs each # for looping for num in 1. 5 puts num end puts num # => 5 # each iterator [1, 2, 3, 4, 5].each do |num| puts num end puts num # => undefined local variable or method `n' for main:Object (NameError) Imagine you want to store the integer 1 in a variable. But maybe now you want to store 2. And 3, 4, 5 …

Do I have a way to store all the integers that I want, but not in millions of variables? Ruby has an answer!

Array is a collection that can be used to store a list of values (like these integers). So let’s use it!

my_integers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] It is really simple. We created an array and stored it in _myinteger.

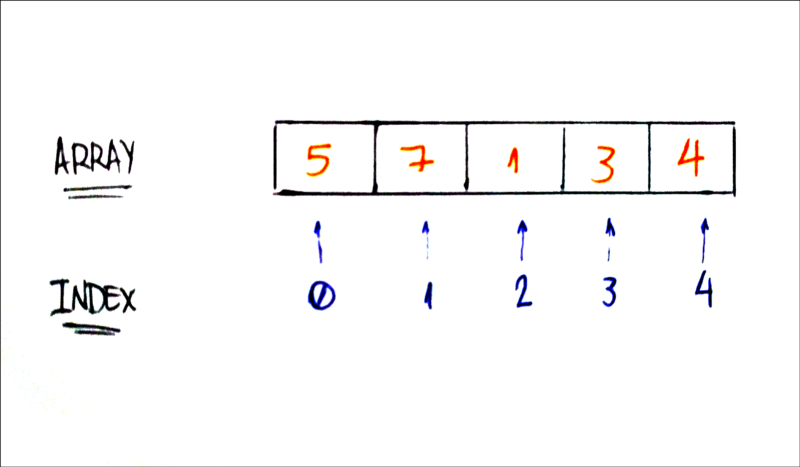

You may be asking, “How can I get a value from this array?” Great question. Arrays have a concept called index. The first element gets the index 0 (zero). The second gets 1, and so on. You get the idea!

Using the Ruby syntax, it’s simple to understand:

my_integers = [5, 7, 1, 3, 4] print my_integers[0] # 5 print my_integers[1] # 7 print my_integers[4] # 4 Imagine you want to store strings instead of integers, like a list of your relatives’ names. Mine would be something like this:

relatives_names = [ "Toshiaki", "Juliana", "Yuji", "Bruno", "Kaio" ] print relatives_names[4] # Kaio Works the same way as integers. Nice!

We just learned how array indices works. Now let’s add elements to the array data structure (items to the list).

The most common methods to add a new value to an array are push and

Push is super simple! You just need to pass the element (The Effective Engineer) as the push parameter:

bookshelf = [] bookshelf.push("The Effective Engineer") bookshelf.push("The 4 hours work week") print bookshelf[0] # The Effective Engineer print bookshelf[1] # The 4 hours work week bookshelf = [] bookshelf "Lean Startup" bookshelf "Zero to One" print bookshelf[0] # Lean Startup print bookshelf[1] # Zero to One You may ask, “But it doesn’t use the dot notation like other methods do. How could it be a method?” Nice question! Writing this:

bookshelf "Hooked" …is similar to writing this:

bookshelf.<<("Hooked") Ruby is so great, huh?

Well, enough arrays. Let’s talk about another data structure.

We know that arrays are indexed with numbers. But what if we don’t want to use numbers as indices? Some data structures can use numeric, string, or other types of indices. The hash data structure is one of them.

Hash is a collection of key-value pairs. It looks like this:

hash_example = < "key1" => "value1", "key2" => "value2", "key3" => "value3" > The key is the index pointing to the value. How do we access the hash value? Using the key!

Here’s a hash about me. My name, nickname, and nationality are the hash’s keys.

hash_tk = < "name" => "Leandro", "nickname" => "Tk", "nationality" => "Brazilian" > print "My name is #"name" ]>" # My name is Leandro print "But you can call me #"nickname" ]>" # But you can call me Tk print "And by the way I'm #"nationality" ]>" # And by the way I'm Brazilian In the above example I printed a phrase about me using all the values stored in the hash.

Another cool thing about hashes is that we can use anything as the value. I’ll add the key “age” and my real integer age (24).

hash_tk = < "name" => "Leandro", "nickname" => "Tk", "nationality" => "Brazilian", "age" => 24 > print "My name is #"name" ]>" # My name is Leandro print "But you can call me #"nickname" ]>" # But you can call me Tk print "And by the way I'm #"age" ]> and #"nationality" ]>" # And by the way I'm 24 and Brazilian Let’s learn how to add elements to a hash. The key pointing to a value is a big part of what hash is — and the same goes for when we want to add elements to it.

hash_tk = < "name" => "Leandro", "nickname" => "Tk", "nationality" => "Brazilian" > hash_tk["age"] = 24 print hash_tk # < "name" =>"Leandro", "nickname" => "Tk", "nationality" => "Brazilian", "age" => 24 > We just need to assign a value to a hash key. Nothing complicated here, right?

The array iteration is very simple. Ruby developers commonly use the each iterator. Let’s do it:

bookshelf = [ "The Effective Engineer", "The 4 hours work week", "Zero to One", "Lean Startup", "Hooked" ] bookshelf.each do |book| puts book end The each iterator works by passing array elements as parameters in the block. In the above example, we print each element.

For hash data structure, we can also use the each iterator by passing two parameters to the block: the key and the value. Here’s an example:

hash = < "some_key" => "some_value" > hash.each < |key, value| puts "# : # " > # some_key: some_value We named the two parameters as key and value, but it’s not necessary. We can name them anything:

hash_tk = < "name" => "Leandro", "nickname" => "Tk", "nationality" => "Brazilian", "age" => 24 > hash_tk.each do |attribute, value| puts "# : # " end You can see we used attribute as a parameter for the hash key and it works properly. Great!

As an object oriented programming language, Ruby uses the concepts of class and object.

“Class” is a way to define objects. In the real world there are many objects of the same type. Like vehicles, dogs, bikes. Each vehicle has similar components (wheels, doors, engine).

“Objects” have two main characteristics: data and behavior. Vehicles have data like number of wheels and number of doors. They also have behavior like accelerating and stopping.

In object oriented programming we call data “attributes” and behavior “methods.”

Let’s understand Ruby syntax for classes:

class Vehicle end We define Vehicle with class statement and finish with end. Easy!

And objects are instances of a class. We create an instance by calling the .new method.

vehicle = Vehicle.new Here vehicle is an object (or instance) of the class Vehicle.

Our vehicle class will have 4 attributes: Wheels, type of tank, seating capacity, and maximum velocity.

Let’s define our class Vehicle to receive data and instantiate it.

class Vehicle def initialize(number_of_wheels, type_of_tank, seating_capacity, maximum_velocity) @number_of_wheels = number_of_wheels @type_of_tank = type_of_tank @seating_capacity = seating_capacity @maximum_velocity = maximum_velocity end end We use the initialize method. We call it a constructor method so when we create the vehicle object, we can define its attributes.

Imagine that you love the Tesla Model S and want to create this kind of object. It has 4 wheels. Its tank type is electric energy. It has space for 5 seats and a maximum velocity is 250km/hour (155 mph). Let’s create the object tesla_model_s! :)

tesla_model_s = Vehicle.new(4, 'electric', 5, 250) 4 wheels + electric tank + 5 seats + 250km/hour maximum speed = tesla_model_s.

tesla_model_s # => @number_of_wheels=4, @type_of_tank="electric", @seating_capacity=5, @maximum_velocity=250> We’ve set the Tesla’s attributes. But how do we access them?

We send a message to the object asking about them. We call it a method. It’s the object’s behavior. Let’s implement it!

class Vehicle def initialize(number_of_wheels, type_of_tank, seating_capacity, maximum_velocity) @number_of_wheels = number_of_wheels @type_of_tank = type_of_tank @seating_capacity = seating_capacity @maximum_velocity = maximum_velocity end def number_of_wheels @number_of_wheels end def set_number_of_wheels=(number) @number_of_wheels = number end end This is an implementation of two methods: number_of_wheels and set_number_of_wheels. We call it “getter” and “setter.” First we get the attribute value, and second, we set a value for the attribute.

In Ruby, we can do that without methods using attr_reader, attr_writer and attr_accessor. Let’s see it with code!

class Vehicle attr_reader :number_of_wheels def initialize(number_of_wheels, type_of_tank, seating_capacity, maximum_velocity) @number_of_wheels = number_of_wheels @type_of_tank = type_of_tank @seating_capacity = seating_capacity @maximum_velocity = maximum_velocity end end tesla_model_s = Vehicle.new(4, 'electric', 5, 250) tesla_model_s.number_of_wheels # => 4 class Vehicle attr_writer :number_of_wheels def initialize(number_of_wheels, type_of_tank, seating_capacity, maximum_velocity) @number_of_wheels = number_of_wheels @type_of_tank = type_of_tank @seating_capacity = seating_capacity @maximum_velocity = maximum_velocity end end # number_of_wheels equals 4 tesla_model_s = Vehicle.new(4, 'electric', 5, 250) tesla_model_s # => @number_of_wheels=4, @type_of_tank="electric", @seating_capacity=5, @maximum_velocity=250> # number_of_wheels equals 3 tesla_model_s.number_of_wheels = 3 tesla_model_s # => @number_of_wheels=3, @type_of_tank="electric", @seating_capacity=5, @maximum_velocity=250> class Vehicle attr_accessor :number_of_wheels def initialize(number_of_wheels, type_of_tank, seating_capacity, maximum_velocity) @number_of_wheels = number_of_wheels @type_of_tank = type_of_tank @seating_capacity = seating_capacity @maximum_velocity = maximum_velocity end end # number_of_wheels equals 4 tesla_model_s = Vehicle.new(4, 'electric', 5, 250) tesla_model_s.number_of_wheels # => 4 # number_of_wheels equals 3 tesla_model_s.number_of_wheels = 3 tesla_model_s.number_of_wheels # => 3 So now we’ve learned how to get attribute values, implement the getter and setter methods, and use attr (reader, writer, and accessor).

We can also use methods to do other things — like a “make_noise” method. Let’s see it!

class Vehicle def initialize(number_of_wheels, type_of_tank, seating_capacity, maximum_velocity) @number_of_wheels = number_of_wheels @type_of_tank = type_of_tank @seating_capacity = seating_capacity @maximum_velocity = maximum_velocity end def make_noise "VRRRRUUUUM" end end When we call this method, it just returns a string “VRRRRUUUUM”.

v = Vehicle.new(4, 'gasoline', 5, 180) v.make_noise # => "VRRRRUUUUM" Encapsulation is a way to restrict direct access to objects’ data and methods. At the same time it facilitates operation on that data (objects’ methods).

Encapsulation can be used to hide data members and members function…Encapsulation means that the internal representation of an object is generally hidden from view outside of the object’s definition.

— Wikipedia

So all internal representation of an object is hidden from the outside, only the object can interact with its internal data.

In Ruby we use methods to directly access data. Let’s see an example:

class Person def initialize(name, age) @name = name @age = age end end We just implemented this Person class. And as we’ve learned, to create the object person, we use the new method and pass the parameters.

tk = Person.new("Leandro Tk", 24) So I created me! :) The tk object! Passing my name and my age. But how can I access this information? My first attempt is to call the name and age methods.

tk.name > NoMethodError: undefined method `name' for # We can’t do it! We didn’t implement the name (and the age) method.

Remember when I said “In Ruby we use methods to directly access data?” To access the tk name and age we need to implement those methods on our Person class.

class Person def initialize(name, age) @name = name @age = age end def name @name end def age @age end end Now we can directly access this information. With encapsulation we can ensure that the object (tk in this case) is only allowed to access name and age. The internal representation of the object is hidden from the outside.

Certain objects have something in common. Behavior and characteristics.

For example, I inherited some characteristics and behaviors from my father — like his eyes and hair. And behaviors like impatience and introversion.

In object oriented programming, classes can inherit common characteristics (data) and behavior (methods) from another class.

Let’s see another example and implement it in Ruby.

Imagine a car. Number of wheels, seating capacity and maximum velocity are all attributes of a car.

class Car attr_accessor :number_of_wheels, :seating_capacity, :maximum_velocity def initialize(number_of_wheels, seating_capacity, maximum_velocity) @number_of_wheels = number_of_wheels @seating_capacity = seating_capacity @maximum_velocity = maximum_velocity end end Our Car class implemented! :)

my_car = Car.new(4, 5, 250) my_car.number_of_wheels # 4 my_car.seating_capacity # 5 my_car.maximum_velocity # 250 Instantiated, we can use all methods created! Nice!

class ElectricCar < Carend Simple as that! We don’t need to implement the initialize method and any other method, because this class already has it (inherited from the Car class). Let’s prove it!

tesla_model_s = ElectricCar.new(4, 5, 250) tesla_model_s.number_of_wheels # 4 tesla_model_s.seating_capacity # 5 tesla_model_s.maximum_velocity # 250 We can think of a module as a toolbox that contains a set of constants and methods.

An example of a Ruby module is Math. We can access the constant PI:

Math::PI # > 3.141592653589793 And the .sqrt method:

Math.sqrt(9) # 3.0 And we can implement our own module and use it in classes. We have a RunnerAthlete class:

class RunnerAthlete def initialize(name) @name = name end end And implement a module Skill to have the average_speed method.

module Skill def average_speed puts "My average speed is 20mph" end end How do we add the module to our classes so it has this behavior (average_speed method)? We just include it!

class RunnerAthlete include Skill def initialize(name) @name = name end end See the “include Skill”! And now we can use this method in our instance of RunnerAthlete class.

mohamed = RunnerAthlete.new("Mohamed Farah") mohamed.average_speed # "My average speed is 20mph" Yay! To finish modules, we need to understand the following:

We learned A LOT of things here!

Congrats! You completed this dense piece of content about Ruby! We learned a lot here. Hope you liked it.

Have fun, keep learning, and always keep coding!